When ICE Comes to Town

It is the job of school boards to ensure that their district has policies to make schools safe and welcoming. That is challenging in a time when some of their students fear that they or their family members are about to be deported.

Photo by the Guardian

Background

Public schools are under a legal obligation to educate all the children in their districts regardless of immigration status. In Plyler v Doe, the Supreme Court ruled that schools may not discriminate on the basis of immigration status. They are forbidden to ask parents or students about their status or to ask for such information as Social Security numbers that might indicate immigration status. The Supreme Court’s rationale at the time–1982–was that children who are denied an education because of a trait that they cannot control (the immigration status of their parents) will not be able to contribute to civic institutions when they grow up, which would be a greater loss than the cost of educating them now.

However, the recent surge of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Border Patrol agents into Los Angeles, Chicago, New Orleans, and Minneapolis and elsewhere has made many families fearful that if they take their children to school they could be swept up in deportation efforts, whether or not they are in the United States legally. Stories from Minnesota in particular make it clear that citizens, refugees, and people who are going through the legal immigration process are at some of the same risk as those who came across the border hoping not to be noticed–whether last year or thirty years ago.

As a result, attendance among children in immigrant families has dropped, which means it is very difficult for districts to provide an education to some of their students..

At one time, the Department of Homeland Security had guidelines prohibiting ICE agents from entering “sensitive locations” such as schools, playgrounds, school bus stops, and childcare facilities. On his first day in office, President Trump rescinded that guideline, which makes it more likely that ICE agents will show up in schools.

The superintendent of Minneapolis said on national television that she has seen ICE agents circling schools, residents of Ypsilanti Michigan have reported ICE agents at school bus stops, and the superintendent of Los Angeles reported that ICE agents have demanded entry into schools.

Possible questions for school board members to ask the superintendent, general counsel, and community support groups:

Are staff trained to not ask parents enrolling their children for immigration status or the kinds of information that might indicate immigration status, such as Social Security numbers?

Has the district trained faculty and staff–including bus drivers, school secretaries, and school crossing guards–what to do if ICE shows up at a school building or a school bus stop?

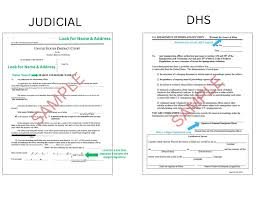

Has the district provided training for the school community about their rights under the Constitution? For example, the Fourth Amendment protects against arbitrary search and seizure, which means that agents of the state are supposed to have a valid warrant before demanding entry into a home or workplace. A valid warrant is one with the name of the court, the signature of a judge or magistrate, an accurate description of the place to be searched (for example a correct address) and a stamp saying when it was filed before demanding entry into a home or workplace. The administrative warrants being used by ICE, signed by an ICE officer, are not sufficient to demand entry into a home or workplace. (This question will no doubt be litigated fairly soon.)

See below for examples of the two different kinds of warrants, courtesy of the ACLU of Pennsylvania.

Do staff keep school doors locked and know to call the district office immediately if ICE arrives, including at evening events such as basketball games? Does district staff know to call the general counsel? Are the numbers to call posted where all staff easily sees them? Does your general counsel provide coverage during out-of-business hours for these kinds of occasions?

Is there a partnership with the local police department to prevent ICE from entering schools without a warrant? Is your state one where the local police are partnering with ICE?

Is there a process to keep students’ emergency contact numbers updated so that if a parent, child, or staff member is seized, the school knows who to notify? Are there policies and procedures to keep this information confidential so that ICE cannot use it to lure family members out of hiding?

Are there procedures in place of who to call if a parent is seized and a child has no one to pick them up from school or provide a safe haven?

Are there local civic groups helping families draw up guardianship papers to ensure any children whose parents have been deported have legal guardians who can direct their schooling? If so, does the district have a way to inform families about those groups?

Are civic organizations providing food and other services to families afraid to leave their homes? Does the district have a way to inform families about those groups?

Are the district’s policies protecting student records sufficient?

Are there policies in place to ensure that students who are absent out of fear of ICE are not counted as having unexcused absences?

Is there a policy to provide on-line schooling to those students who are not attending school because of fear of deportation? (Minneapolis and St. Paul and other districts have provided hybrid learning.)

Are there policies to ensure that the on-line learning is as robust as possible?

For further information:

The ACLU of Ohio wrote a very clear memo laying out what federal law is and what the legal requirements of American schools are.

The Advancement Project has a comprehensive “Protecting Immigrant Students Action Kit” with possible school and district policies and procedures for school staff members.

The Immigrant Legal Resources Center has a useful Family Preparedness Plan with step-by-step directions for arranging for guardianship and other ways to plan for if a family member is deported or detained.